Saturday, November 10, 2007

"Searching for tūpuna : Whakapapa researchers in public libraries", completed research project

This is an academic work and may be used for educational and academic purposes as long as it is appropriately referenced and cited.

A paper copy of this report is also held by the Victoria University of Wellington Campus Library.

For further information or enquiries regarding this research, please contact the researcher.

Whakapapa researchers and public libraries

by

Moata Tamaira

Submitted to the School of Information Management,

Victoria University of Wellington

in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Library and Information Studies

October 2007

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the contribution made by the membership of the Māori Interest Group of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists, in particular “Te Reo” editor Bruce Mathers and MIG secretary Brenda Joyce. Your enthusiasm and interest made me determined to soldier on. Also, to the members of Te Rōpū Whakahau who helped by asking questions, or filling out pilot surveys, many thanks.

To the managers who kindly gave their permission for me to distribute my questionnaire in their institutions, Bernie Hawke, Joanne Horner, Carolyn Robertson, Whina Te Whiu, and in particular Raewyn Paewai for her seemingly endless enthusiasm. I could not have undertaken this project without your support or that of your staff, particularly Ann Reweti, and Jean Strachan.

To my colleagues at Christchurch City Libraries for their willingness to accommodate my study needs, and for their unending patience and support, I am fortunate to work alongside you in this crazy library business. And finally, to my friends and family, I couldn’t have done it without you. Arohanui ki a koutou katoa.

Moata Tamaira

2007

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Problem

2.1 Problem Statement

2.2 Research Objectives

2.3 Research Questions

2.4 Expected benefits of the research

2.5 Definitions

2.6 Limitations and delimitations

2.6.1 The limitations of this study

2.6.2 Delimitations of this study

3. Literature Review

3.1 Whakapapa in Māori Culture

3.2 Genealogists and Family Historians

3.4 Indigenous Populations and Libraries Internationally

3.5 Māori, Information Management, and Technology

3.6 Summary

4. Research Design

4.1 Project Description

4.2 Methodology

4.2.1 Survey

4.2.1.1 Pilot survey

4.2.1.2 Survey instrument - Printed

4.2.1.3 Survey instrument - Online

4.2.1.4 Survey content

4.3 Population and Sample

5. Data Analysis

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Whakapapa Researcher Profile

5.2.1 Age, Gender and Ethnicity

5.2.2 Previous research experience

5.2.3 Motivation for beginning whakapapa research

5.2.4 Whose ancestors are being researched?

5.3 Whakapapa research experience

5.3.1 Level of whakapapa research experience

5.3.2 Whakapapa research in public libraries

5.4 Finding whakapapa information in public libraries

5.4.1 Order of research activity in the library

5.4.2 Using whakapapa sources

5.4.3 Using sources of information effectively

5.4.4 Librarian produced materials used by whakapapa researchers

5.4.5 Asking a librarian for help

5.5 Computer knowledge and experience

5.5.1 General computer experience

5.5.2 Use of the library catalogue

6. Conclusions and recommendations

6.2 Summary of the data

6.3 Recommendations

6.4 Further research

Appendices

Appendix 1. Letter of Information

Appendix 2. Survey Questionnaire

Appendix 3. Aggregate data for Question 10

Bibliography

Abstract

Similar research methodologies as have been used overseas have been utilised in this piece of research with respect to genealogists in New Zealand, specifically those researching the family history of Māori, the indigenous people of that country. In traditional Māori culture great significance is placed on family history or whakapapa. This study aimed to investigate to what degree the use of public libraries by genealogists researching this cultural group reflected findings of library use and information seeking behaviour of genealogists in other cultural environments. Whakapapa research may be undertaken by genealogists who do not have Māori ancestors, or tūpuna, themselves and these library users still fall within the scope of this study.

Data was collected by using printed questionnaires distributed to public libraries in New Zealand, as well as a printable version of the questionnaire that was made available online .

Keywords: genealogists, family historians, indigenous, Māori, libraries, whakapapa

1. Introduction

2.1 Problem Statement

[1] Estimates from Statistics New Zealand (2005) (pg. 142) anticipate Māori rising to 29% of the population by 2021.

2.2 Research Objectives

- find out how whakapapa researchers use public library services.

- compare the results relating to whakapapa researchers with those found in literature on genealogists in general to illuminate any differences between these groups of library users.

- use the data collected and resulting analysis to create a picture of what steps public libraries might take to enhance their services to this user group.

2.3 Research Questions

In support of the objectives stated above the following questions will be addressed in the course of the study.

- What is the profile of the whakapapa researcher, in terms of age, gender, ethnicity, level of research experience, and motivations?

- What key sources do whakapapa researchers seek out and use in public libraries?

- What resources do whakapapa researchers use in public libraries?

- What search strategies do whakapapa researchers employ?

- Are whakapapa researchers confident users of information technology?

To a large degree these research questions mirror those used by Kuglin (2004) in order to compile similar data sets that lend themselves well to comparison in the analysis phase of the study.

2.4 Expected benefits of the research

2.5 Definitions

Genealogy is the study of lineage of one or more families, often with the view to creating a family tree or pedigree chart.

Family history relates to, but is not the same as, genealogy. Where genealogy is concerned strictly with lineage, family history allows for the inclusion of broader contextual information about families and individuals.

Information seeking behaviours refers to the strategies that researchers employ in finding the sources that will further their research. This may include the use of a range of resources.

Public libraries refers to those libraries that are funded by local government rather than libraries that are accessible to the general public.

Resource is an item that has been produced by the library or librarian to help researchers find specific sources within the library collection. Printed or website based guides, archival finding aides, and computer catalogues are all examples of resources.

“Source is a published or unpublished item purchased or acquired by a library as a part of its colleciton and is catalogued” Kuglin (2004). Examples of whakapapa sources include Māori Land Court records, Birth, death, and marriage records, and published genealogies of Māori families.

Search strategies are those patterns of information seeking behaviour that are favoured by the researchers in question. Search strategies will relate to the use of resources within the public library setting such as use of computer catalogues etc.

Whakapapa is a Māori word meaning family history or genealogy, although it can also apply in contexts other than genealogy.

Whakapapa researchers are researchers, either professional or amateur, who study and investigate the family history and lineage of Māori New Zealanders either regarding their own ancestry or someone elses.

2.6.1 The limitations of this study

There was the possibility of there being some self-selection bias. Possibly more experienced whakapapa researchers would be more likely to complete the survey as a result of their greater commitment and interest in the subject. Again the provision of an online distribution point for the survey could have made it more likely for younger researchers to participate. The use of an online survey by Drake (2001) had this effect and on the whole younger researchers will have been involved in their research for less time so responses from less experienced researchers might be more likely as a result.

As several distribution points for the survey were chosen from around the country, the researcher was unable to attend to these personally. This was potentially problematic in terms of consistency of promotion around the various sites. Also communication between the researcher and distribution points was very important in order to keep to prescribed timetables.

2.6.2 Delimitations of this study

This research project focuses on whakapapa researchers in New Zealand. The bulk of information sources for Māori family history will be located in New Zealand though information may also be available in institutions overseas. In addition significant numbers of Māori, and by extension whakapapa researchers, live in other countries, particularly Australia where almost 73,000 people of Māori descent live[1]. This project is not concerned with ex-patriate whakapapa researchers and looks specifically at those using New Zealand public libraries.

[1] from Australian Bureau of Statistics (2006)

3. Literature Review

3.1 Whakapapa in Māori Culture

3.2 Genealogists and Family Historians

Despite the long association that genealogists and family historians have had with libraries and archives surprising little research has looked at what sorts of information seeking behaviours these customers utilise, that is, what strategies genealogists use in trying to find the family history information they need. Duff and Johnson (2003) conducted a series of in-depth interviews with American professional genealogists and determined that this group tended not to use librarian-produced finding aids, and tended to rely “more heavily on colleagues or an informal network than on archivists” (pg. 94). Duff and Johnson also found that these highly experienced genealogists were very adept at re-framing their information need, such as the name of an individual being researched, into a search for the kind of record that might contain that information, such as a baptism or marriage record. This research was conducted within the context of the use of archives rather than libraries, as well as focusing on experienced users. Kuglin (2004) finds some similarities within the use of libraries in New Zealand specifically in that family historians and genealogists tend to be “quite independent researchers” (pg. 67) with relatively low use of finding aids. The information seeking behaviour of whakapapa researchers has however not be investigated in any of the current literature.

Research on genealogists often focuses on generating a genealogist “profile” and determining their level of involvement in genealogical research. Lambert (1999), Yakel (2004), Drake (2001), and Kuglin (2004) all incorporate a profiling aspect in their research. Drake’s survey sought to elicit information about genealogists themselves as well as their level of involvement in genealogy. Drake’s was the only study to use an online survey and notably received the highest number of respondents of the three. Kuglin (2004) dedicates a portion of her research to creating a genealogist “profile” with data gained through a survey distributed in several New Zealand libraries. Each of these studies, though using different methods of delivery, often in different countries all paint a similar genealogist “portrait” of a genealogist as an older woman who spends a signficant amount of time on her hobby and is relatively experienced in family history research.

Kuglin’s (2004) research stands out as the sole piece of research on genealogists and their use of library services that is set in New Zealand. Apart from creating a genealogist “profile” the study sought to determinine how genealogists research in libraries and how experienced they are, in order to better understand their informational needs and how to address them. Her conclusion that genealogists would benefit from collaboration between libraries and genealogical societies mirrors Litzer’s (1997) findings. Unfortunately the demographic data gained from informants in this study was restricted to age and gender therefore cultural considerations as relates to genealogists researching Māori family history were not illuminated. Furthermore, Kuglin admits that her survey did not capture sufficient data from inexperienced genealogists and that it paints an incomplete picture that warrants further investigaton. Kuglin’s study is also limited geographically to the North Island, and can therefore only represent a part of the overall picture for the country.

3.4 Indigenous Populations and Libraries Internationally

3.5 Māori, Information Management, and Technology

Two key, related pieces of research that do focus on public libraries have been published. MacDonald’s (1993) research used interviews and surveys filled in by staff in public libraries in order to determine how well libraries were catering to Māori customers. Though it highlighted several key points in library use by Māori, its focus was mainly on those providing the service, and whakapapa research was not dealt with. In Szekely’s (1997) follow-up study the opinions of both Māori staff and users of the library were gathered through a series of hui or meetings held throughout the country. This piece of research highlighted several issues that apply to the study currently being proposed such as the identification of whakapapa as an “Information need” (pg. 36), attitudes around the appropriateness of libraries holding this information, and a general reticence by Māori in using libraries. Similarly Auckland City Libraries in consultation with Heather Worth (1995) surveyed their customers about their use of that public library network and received similar feedback. No further follow up research has been undertaken in these areas and ten years on it may be timely to revisit some aspects of this research study with a focus on whakapapa researchers. Also discussed by Szekely was the difficulty Māori have in dealing with technology such as library catalogues, an idea supported by Duncker’s (2002) and Simpson’s (2005) findings.

Recent research by Ta’ala (2006) has illuminated the changing role of whakapapa in a records management context. Ta’ala conducted a series of interviews with representatives of Iwi rūnanga (Māori tribal organisations) to determine how whakapapa, a mainstain of a traditional Māori worldview, was being changed by its integration within a western records management system and how tikanga Māori (traditional Māori beliefs and protocols) has been applied in the care of Māori information. Though this research takes place in the context of records management there are aspects of this that could be relevant to public libraries also.

Māori access to technology is the focus of the work of Parker (2003) who used data gathered from interviews and surveys to assess the engagement of Māori with information technologies and found that this demographic suffers from a noticeable “digital divide” meaning that Māori are far less likely to have access to information technologies than the population in general. Public libraries extensively use these technologies in providing access to resources, as well as providing access to the technologies themselves. No research in this area has yet determined how this trend might affect whakapapa researchers.

3.6 Summary

4.1 Project Description

The population that is the focus of the project is smaller than in Kuglin’s study because the percentage of New Zealanders who identify as Māori is 14.7% of the total population, according to statistics gathered during the 2001 census by Statistics New Zealand (2002) (pg. 11). Kuglin’s research gathered data from any genealogists regardless of their specific area of interest or ethnicity. This being the case, it was considered necessary to cast a wider net to capture data than was utilised in Kuglin’s study. For this reason the study had a broader geographical focus. In addition, with regards to the survey instrument, where other research indicated, or researcher experience suggested that additional or modified questions should be used or other adjustments made, these were incorporated into the study.

A pilot study was employed to check the feasibility of the questionnaire used and that individual questions were acceptable. After the revised questionnaire (Appendix 2) was distributed and the data was collected, the analysis phase began which involved grouping, and collating data into sets to provide a comparison to the data collected in Kuglin’s research. In some cases exact correlations were not possible as modifications to Kuglin’s original questionnaire were made but comparable results should be possible in areas such as the creation of a researcher “profile” and in identifying levels of use of specific resources.

In the last phase of the study the analysed data, along with the researcher’s own public library experience, and other literature in the field was used to formulate a series of recommendations. These recommendations take the form of key actions or processes that public libraries can take to improve their service to whakapapa researchers.

4.2 Methodology

4.2.1 Survey

4.2.1.1 Pilot Survey

One respondent found that Question 1, option a. “for posterity” might not be clear to all potential respondents and that this could be explained in more detail. As a result a fuller explanation of the term was included in this question option. Another respondent felt that the year range offered in Question 2 which asked how long someone had been involved in whakapapa research was too narrow. Given that past research, as mentioned earlier, has profiled genealogists as being “elderly” it was considered a fair point to make and as a result the year range was extended by 5 years.

All respondents to the pilot survey completed the questionnaire fully and were able to follow the instructions well. Estimates on how long respondents took to fill in the questionnaire ranged from 5 to 15 minutes. These results suggested that the questionnaire, with minor adjustments, would be suitable for wider distribution

4.1.1.2 Survey Instrument – Printed

In keeping with Kuglin’s study, the individual libraries in which the survey was distributed were the “main” or central library where the core New Zealand (and therefore Māori) heritage resources are held. These libraries were –

- Auckland City Libraries, Central City Library, Auckland Research Centre

- Manukau Libraries, Central Research Library

- Wellington City Libraries, Central City library, New Zealand Collection

- Christchurch City Libraries, Central City library, Aotearoa New Zealand Centre

- Dunedin Public Libraries, City library, 3rd floor

A dropbox was made available at each of these distribution points for respondents to use but a freepost address and self addressed envelopes were also provided as Kuglin’s experience showed that many more surveys were submitted via mail than were deposited in the boxes provided. In this study this proved not to be the case, though some completed questionnaires were received in this way, particularly those accessed online. In addition Kuglin’s use of different coloured paper for different locations was employed in this study to help increase efficiency in the data analysis phase of the project. In order to gather enough completed questionnaires to have a large enough sample to work with (see 4.2 Population and sample) 40 questionnaires be distributed to each of these sites.

Distribution of the printed survey occurred between 16 August 2007 and 5 September 2007 with the cut-off date for receipt of completed surveys set at 10 September 2007.

4.1.1.3 Survey Instrument – Online

Though Kuglin used local branch meetings of the NZSG to distribute questionnaires directly to genealogists, this was not an option in this research. Because the sites of distribution used in this study were spread across the country it was practical for the Christchurch based researcher to attend local meetings. In addition the Māori Interest Group, which comprises of whakapapa researchers and is therefore the target demographic for the questionnaire, is a national group of roughly 50 individuals[1], spread geographically across the country. It was not possible for the researcher to attend a branch meeting as the members of this group do not regularly meet. The possibility of utilising the group’s mailing list to send questionnaires directly to group members was also out of the question as this would contravene the Privacy act (1993) and as a result it was decided that a PDF version hosted from the the group’s website would be the best way to make it available to members, as well as to interested non-members.

As well as making the members of MIG-NZSG aware of the questionnaire through their newsletter links to the PDF document were posted on the researcher’s project blog www.searching4tupuna.blogspot.com and via the noticeboard of an online whakapapa club http://whakapapa.maori.org.nz/ .

[1] Joyce (2007)

4.1.1.4 Survey Content

- Whakapapa research experience and interest

- Finding the information you need in the library

- Librarian provided assistance

- Computer knowledge and experience

- General information about you

However there were changes to question options provided to make them more relevant to users of Māori information sources, and where necessary additional questions were included, for instance in the “General information about you” section, in order to highlight demographic information needed to answer the research questions of the study. Some questions used in Kuglin’s study were omitted in the interests of keeping the questionnaire to a size that would not make it too time consuming for respondents to complete.

4.2 Population and Sample

5.1 Introduction

In most cases the gathered and analysed data has been expressed as percentages. This method has the advantage of making comparisons with data gathered in earlier studies such as Kuglin’s easier despite there being different levels of response involved. Where percentages have been used these have been rounded to the nearest whole number. In circumstances where this rounding caused either a slight excess or deficit, with the total percentages adding up to more or less than 100 percent, the difference has been subtracted or added to the option with the largest percentage result. In keeping with Kuglin’s study the data has been represented in the form of graphs or tables.

Where a question was not fully completed or missed by a respondent this question has been considered void. Other questions on the same questionnaire were still included for analysis assuming that they were filled in correctly. It was anticipated that at least some of the survey questions would be inaccurately completed by respondents but the inclusion of a pilot study was considered to have lessened the likelihood of this occurring.

It was hoped that the utilisation of 5 distribution sites at public libraries in different parts of the country would create a fuller picture of whakapapa researchers around the country, however there was much variability in response at different sites. Despite questionnaires being prominently displayed in the Genealogy Room of the City Library no responses were received from Dunedin Public Library customers. This is almost certainly to do with the much lower level of Māori population in this city than in others, with only 1.2% of the Māori population of New Zealand residing in this city[1]. As a result no data for Dunedin Public Library customers was gathered and will not feature in the analysed data.

There were also no responses from Auckland City Libraries customers. Unfortunately questionnaires completed by these respondents were not returned in time to be included in this research. Auckland City Libraries customers completed 15 questionnaires but they do not feature in the analysed data. The researcher hopes to be able to incorporate this data into any future articles or conference presentations on this topic.

Of the remaining 3 libraries that did manage to garner customer responses, the only site that reached the target of 12 or more completed questionnaires was Manukau Libraries which was the source of 13 completed questionnaires. Given that Manukau is home to 8.4% of the Māori population of New Zealand[2] this higher number of responses is not surprising. Christchurch City Libraries customers completed and returned 11 questionnaires and Wellington City Libraries customers completed 3 questionnaires. In addition 5 respondents used the questionnaire that was made available online. The following analyses is based on these 32 responses, though some individual questions may have slightly fewer responses due to questions being incorrectly completed in some cases.

It was hoped that some comparison would be able to be made between Māori and non-Māori respondents however only 3 individuals identified as non-Māori and this small number was not considered by the researcher to be significant enough that conclusions could be confidently drawn from this data. Similarly the small number of responses from the Wellington distribution site meant that analysing data specifically from this site was problematic in terms of being statistically meaningful. However the number of responses from the Christchurch and Manukau sites meant that trends and/or patterns of data for these sites were more obvious.

In keeping with Kuglin’s study the level of research experience of whakapapa researchers was investigated in terms of the length of time that the respondent had been involved in the “hobby”, how often they visited a public library for the purpose of this research, and how much time was spent there, and how much research experience these researchers had prior to their interest in whakapapa. In addition, the strategies and behaviours that whakapapa researchers utilise when they are in a public library are examined by looking at the what research activity they employ on their first and subsequent visits to an unfamiliar library, by determining their preferred methods of locating relevant resources, be it by shelf-browsing or library catalogue use, as well as the level of information literacy employed by researchers in their use of footnotes, bibliographies, and instructions to specific resources. The degree to which whakapapa researchers use computers in their research is also examined.

Demographic information gathered via the questionnaire is used to create a whakapapa researcher “profile” and compared to similar profiles in the existing literature.

[1] Statistics New Zealand (2001)

[2] Statistics New Zealand (2001)

5.2.1 Age, Gender and Ethnicity

Chart 1.

Although the age of whakapapa researchers differs significantly from those investigated in earlier research, in terms of gender, results were quite similar to other studies. In this study there was a slightly lower percentage of female researchers (59%) than Kuglin (2004) and Drake (2001) but this was similar to Lambert’s (1998) results (Chart 2)(Appendix 2, Question 21). In all of the research undertaken female researchers have significantly outnumbered males and this tendency is confirmed by the data in this study also.

Although the age of whakapapa researchers differs significantly from those investigated in earlier research, in terms of gender, results were quite similar to other studies. In this study there was a slightly lower percentage of female researchers (59%) than Kuglin (2004) and Drake (2001) but this was similar to Lambert’s (1998) results (Chart 2)(Appendix 2, Question 21). In all of the research undertaken female researchers have significantly outnumbered males and this tendency is confirmed by the data in this study also.Chart 2.

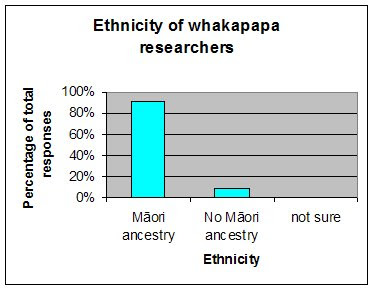

As expected the vast majority of respondents had Māori ancestry (Chart 3). It was the researcher’s experience however, that whakapapa researchers were not exclusively those with Māori ancestry and this was confirmed by the 3 respondents who identified themselves as non-Māori. This question (Appendix 2,Question 23) was included to get some idea of how many whakapapa researchers fit into this category as no previous research has looked at this and it was hoped that data from other questions could be analysed with reference to the ethnicity of the respondent. Due to the small number of non-Māori respondents it was decided that this would not provide meaningful results.

As expected the vast majority of respondents had Māori ancestry (Chart 3). It was the researcher’s experience however, that whakapapa researchers were not exclusively those with Māori ancestry and this was confirmed by the 3 respondents who identified themselves as non-Māori. This question (Appendix 2,Question 23) was included to get some idea of how many whakapapa researchers fit into this category as no previous research has looked at this and it was hoped that data from other questions could be analysed with reference to the ethnicity of the respondent. Due to the small number of non-Māori respondents it was decided that this would not provide meaningful results.Chart 3.

5.2.2 Previous research experience

Chart 4.

5.2.3 Motivation for beginning whakapapa research

Chart 5.

Legend

Legenda. For posterity (to keep a record for future generations)

b. To learn about my roots, about who I am

c. To carry on work already begun by another family/whānau member(s).

d. To keep my whakapapa researcher wife/husband/partner company

e. To trace medical conditions in a family tree

f. For religious/spiritual reasons

g. For employment (as a paid researcher)

h. to meet living relatives

i. Because I enjoy the company of other whakapapa researchers/genealogists

j. I had to provide whakapapa to qualify for an education grant/scholarship (Tamaira study only)

k. I had to provide whakapapa to register with my iwi (Tamaira study only)

Results for this question were quite similar to those found by Kuglin (2004) (Chart 5) with option b “to learn about my roots, about who I am” the most popular answer in both studies. Notably, several respondents in this study felt that religious/spiritual reasons was a motivating factor in their whakapapa research, and though this did not rate as highly as other options it was significantly higher than in Kuglin’s study suggesting that there may well be a spiritual aspect to whakapapa research. Future study might be able to shed more light on this aspect of whakapapa researchers’ motivations. In addition, gaining iwi/tribal benefits were found to be only moderately important motivations for beginning whakapapa researchers.

5.2.4 Whose ancestors are being researched?

Amongst Māori respondents, overwhelmingly researchers were researching their own whakapapa, however not insignificant numbers of respondents reported that they researched on behalf of others, even those not related to themselves (Chart 6). On the whole research was undertaken for themselves and their descendants, which to some degree reflects the popularity of option a “for posterity (to keep a record for future generations)” in question 1 (see 5.2.3 Motivation for beginning whakapapa research).

Chart 6.

Legend

a. my own

b. my spouse/partner’s

c. my friend’s

d. my children’s

e. my grandchildren’s

f. those of other genealogists/whakapapa researchers

g. those of a client, as a paid researcher

5.3.1 Level of whakapapa research experience

Respondents were asked how much time per month they spent on their whakapapa research and how many years they had been researching whakapapa (Appendix 2, Question 3 & 2). In her study Kuglin (2004) took the data from these two questions and established a formula for categorising researchers as either beginner, intermediate, or experienced researchers. Different levels of researcher experience were defined in the following way–

- Beginner researchers were those who spent less than 1 hour per month for up to 4 years on their research.

- Intermediate researchers were those who spent 1 – 3 hours per month for up to 4 years on their research.

- Experienced researchers were those who spent at least 4 hours per month for 3 or more years on their research. (pg. 11)

This researcher found these categories problematic in that not all respondents could be successfully categorised this way. For instance a respondent who had been involved in whakapapa research for over 10 years but only spent 1 – 3 hours per month on their research did not fit into any of these categories. As a result this categorisation as beginner, intermediate, or experienced researcher was not used in this study. As such, comparisons with Kuglin’s results using these categories cannot be made. Instead, comparisons of the results for the individual questions are discussed.

Kuglin (2004) found that 79% of respondents to her questionnaire had been doing their research for 5 years or more. In this study the percentage was significantly less, with only 47% of respondents having been involved in research for that amount of time (Chart 7). This is not so surprising given that Kuglin’s population sample was signifcantly older than the one studied here. When analysed by respondent age, 80% of those who reported they had been involved in whakapapa research for this amount of time were over 40 years of age. Similarly younger respondents were less likely to have spent more than 2 years on this kind of research.

Chart 7.  The amount of time spent on research was also compared, with whakapapa researchers generally spending less hours per month on their research (Chart 8). Taken together, this data suggests that whakapapa researchers have less experience doing their research than genealogy researchers generally. As such they may require more help or guidance from library staff (see 5.4.5 Asking a librarian for help).

The amount of time spent on research was also compared, with whakapapa researchers generally spending less hours per month on their research (Chart 8). Taken together, this data suggests that whakapapa researchers have less experience doing their research than genealogy researchers generally. As such they may require more help or guidance from library staff (see 5.4.5 Asking a librarian for help).

Chart 8.

In addition to the amount of time spent, respondents were also asked about what different institutions they visited to do their research (Appendix 2, Question 4). In determining the level of research experience of respondents Kuglin considered that those visiting numerous different repositories with different classification systems and finding aids would have gained valuable research experience by doing so. For this study the options offered to respondents were adjusted slightly, with options such as a Marae-based library, or Iwi runanga whakapapa unit/office being added. In addition the option of travel overseas was removed since it is assumed that whakapapa research material will be primarily New Zealand based.

The most frequently ticked item was “local public library” with “public library in another city or town” as the second most ticked option (Table 1). Kuglin’s results for this question showed a strong preference for the National Library of New Zealand/Alexander Turnbull Library but this is partly due to most of her respondents being from the Wellington region in which this library is located. Latter Day Saints (Mormon) family history centres also rated highly in that study and received the same number of ticks as “local public library”. This was not the case here, possibly because such centres do not contain as much information about Māori genealogical information as other institutions. Kuglin also found that when the number of items ticked was divided by the number of respondents there was an average of 6 institutions per respondent. In this study 130 items were ticked resulting in an average of 4 institutions per respondent.

Table 1. Institutions used for whakapapa research in order of frequency of choice made by all respondents

The researcher was interested to note that 9 respondents selected public libraries as the only institutions that they used. Of these 9 researchers, 7 had been involved in whakapapa research for less than 2 years. This suggests that the public library is a starting point for some whakapapa researchers. They may use this as jumping off point to visiting other less publicly accessible institutions as their research experience progresses. Whether this is the case cannot be determined from the current study but would be an area for further research. In addition, though this question asks about institutions that respondents have visited 5 respondents wrote in that they had specifically visited whānau/family members or knowledgeable tribal elders for the purpose of researching whakapapa. This is possibly an option or added question that could be included in a future version of the questionnaire. This reflects one of the information seeking behaviours that has been highlighted by researchers like Simpson (2005) and Duncker (2002) with regards to Māori customers preferring to receive information from individuals rather than other resources.

The results from this set of questions, when compared with Kuglin’s (2004) seems to suggest that whakapapa researchers do not have as much research experience in their hobby as genealogists in general.

5.3.2 Whakapapa research in public libraries

Chart 9.

Chart 10.

Chart 10. Despite visiting more often, the amount of time spent per visit by whakapapa researchers compared with genealogists seems to be about the same (Chart 10). In Kuglin’s study just over 50% of respondents spent 2-3 hours per visit. From this data it seems clear that both genealogists and whakapapa researchers are frequent public library visitors who spend significant amounts of time there on their research.

Despite visiting more often, the amount of time spent per visit by whakapapa researchers compared with genealogists seems to be about the same (Chart 10). In Kuglin’s study just over 50% of respondents spent 2-3 hours per visit. From this data it seems clear that both genealogists and whakapapa researchers are frequent public library visitors who spend significant amounts of time there on their research.5.4.1 Order of research activity in the library

Chart 11.

Legend

Legenda. Consult the genealogy reference librarian

b. Consult the Māori reference librarian

c. search the library catalogue

d. browse the genealogy shelves

e. browse the Māori collections shelves

f. look for a brochure or other printed guide to introduce me to the collection

There was also a marked difference from Kuglin’s results which showed that consulting a staff member rated highly as a first visit strategy but dropped in the subsequent visit. This study had opposite results as consulting the Māori reference librarian was the most popular option on the first visit and increased on the subsequent visit. Duncker’s (2002) research at Waikato University that emphasised the importance of face to face (kanohi-ki-te-kanohi) interaction as the preferred method of acquiring information for Māori library users is seemingly supported by this data. Also worth noting was that brochures or printed guides were not the preferred option for any of the respondents. As a first “port of call” in a public library it seems that whakapapa researchers are more interested in speaking with knowledgeable staff members than in printed guides or brochures.

5.4.2 Using whakapapa sources

Table 2. Sources commonly used by whakapapa researchers

It is important that library staff know which sources are likely to be in demand for whakapapa research not only for acquisition of suitable sources but also for improving access to those already owned by the library. The most frequently selected item was Māori Land Court records. There are indexes for some Māori Land Court Minute books, both available as CD-ROM or subscription database. Given that this seems to be a highly used source by whakapapa researchers it will be to their benefit to have access to these indexes. Also, it is worth considering which sources might be better utilised if they were sited within a Māori collection rather than as part of a genealogy collection.

Also worth noting is that both Births, deaths, and marriages indexes and Electoral rolls (2nd and 3rd most selected sources respectively) have sub-sections, or separate indexes for Māori individuals during some time ranges. This means that these very popular sources are potentially more complicated to use for whakapapa researchers, who may have to check both the Māori, and general roll or index. Library staff should be aware of the added complexity of these sources with respect to whakapapa research, as it may mean that more staff help is needed, at least in the beginning.

In Kuglin’s study Census records ranked very highly in this question but did not appear to be a preferred option for whakapapa researchers. This is probably due to the fact that many census records for the United Kingdom, which contain personal information about individuals, are now available online. Though New Zealand census information is only available in the form of aggregate data, and does not feature individuals’ information, some regional historical censuses for Māori populations exist and do contain individual and family names. However these are not widely publicised and are often “buried” within larger works such as Waitangi Tribunal evidence, or the Appendices to the Journal of the House of Representatives. This is most likely the reason that whakapapa researchers do not make use of these kind of records as often as other genealogists might.

Ranking what tools whakapapa researchers used that found most useful information for their research was the subject of the next question (Appendix 2, Question 10). Although there were only 6 options given that respondents needed to rank, this proved difficult for some respondents, with 7 questionnaires being considered void for this question, usually because the same ranking was used for more than one option. The most notable difference between results in this study and Kuglin’s (2004) was the high use of fiche/CD-ROM indexes that Kuglin found. In this study whakapapa researchers surveyed ranked this as lowest. This could be due to the fact that microfiche indexes form a large part of the resources held at Latter Day Saints (Mormon) family history centres, an institution that many respondents in Kuglin’s used.

The table below shows the strategy that received the most ticks for a particular ranking (Table 3). Asking a librarian for help was ranked as the most useful strategy, compared with its third place ranking in Kuglin’s study, though this was the option most often ranked fourth as well. It seems that some whakapapa researchers rate the help of librarians, while others prefer alternate methods (Appendix 3, Aggregate data).

Table 3. Strategy that most frequently finds a source useful to whakapapa research

5.4.3 Using sources of information effectively

Chart 12.

5.4.4 Librarian produced materials used by whakapapa researchers

Table 4. Librarian produced materials used by whakapapa researchers

Interestingly respondents in this study seem to have a preference for a printed list of sources arranged by geographic location. This may be due to the fact that many whakapapa sources are tied closely to tribal rohe/regions and that whakapapa researchers find sources grouped thematically by geography, particularly useful. Guided tours were also ranked quite highly, and this may support the idea that Māori library customers appreciate face to face interaction with librarians while conducting their research. Information on library websites also seem to be well used by whakapapa researchers suggesting that this may be an area that librarians should continue to develop. Very few respondents had found an introductory video or DVD useful to their research but it is not clear whether these are available in many libraries. This could be an area for further study.

5.4.5 Asking a librarian for help

Chart 13.

Respondents were also asked what they asked for librarian assistance with (Appendix 2, Question 14). They were asked to identify 4 reasons that they asked for help but many respondents did not choose 4 options and 2 respondents ticked the “I have never asked a librarian for help” option, in addition to 3 other options. As these answers contradicted themselves these 2 questionnaires were not included in the analysed data for this question (Table 5).

Respondents were also asked what they asked for librarian assistance with (Appendix 2, Question 14). They were asked to identify 4 reasons that they asked for help but many respondents did not choose 4 options and 2 respondents ticked the “I have never asked a librarian for help” option, in addition to 3 other options. As these answers contradicted themselves these 2 questionnaires were not included in the analysed data for this question (Table 5).Table 5. Reasons for asking a librarian for help

Although in both this and Kuglin’s study, finding a source that the respondent already knew the name of was the most often selected option, differences emerge beyond this point. Of note is that finding a whānau/family name was the second equal most selected option in this study but was the least often selected option in Kuglin’s study. This may be due to the fact that in New Zealand Māori surnames are often less common than European names and are often linked to particular geographical or tribal areas. This also has resonance with the research carried out by Duff & Johnson (2003) who found that genealogists using archival material would be greatly helped by indexing or finding aids that focused on personal names. Names are clearly an important entry point for whakapapa researchers also. On the whole technical problems to do with the use of machines and other technology did not rank as highly as requests for help in accessing information. Whakapapa researchers are reasonably likely to ask about how to use a source they have already found, with this option coming third. This is not surprising given their underuse of the instructions and introductions of specific sources as discussed earlier (see 5.4.3 Using sources of information effectively).

Although in both this and Kuglin’s study, finding a source that the respondent already knew the name of was the most often selected option, differences emerge beyond this point. Of note is that finding a whānau/family name was the second equal most selected option in this study but was the least often selected option in Kuglin’s study. This may be due to the fact that in New Zealand Māori surnames are often less common than European names and are often linked to particular geographical or tribal areas. This also has resonance with the research carried out by Duff & Johnson (2003) who found that genealogists using archival material would be greatly helped by indexing or finding aids that focused on personal names. Names are clearly an important entry point for whakapapa researchers also. On the whole technical problems to do with the use of machines and other technology did not rank as highly as requests for help in accessing information. Whakapapa researchers are reasonably likely to ask about how to use a source they have already found, with this option coming third. This is not surprising given their underuse of the instructions and introductions of specific sources as discussed earlier (see 5.4.3 Using sources of information effectively).

5.5 Computer knowledge and experience

5.5.1 General computer experience

Chart 14.

All respondents whose questionnaire was printed from the PDF version made available online rated themselves as “very experienced”. Given that these respondents would have to have found the questionnaire online, download it, and print it out, it is not surprising that these respondents would have at least a moderate level of computing experience. Although data from this question was analysed by age, no noticeable trends were evident across the age ranges.

All respondents whose questionnaire was printed from the PDF version made available online rated themselves as “very experienced”. Given that these respondents would have to have found the questionnaire online, download it, and print it out, it is not surprising that these respondents would have at least a moderate level of computing experience. Although data from this question was analysed by age, no noticeable trends were evident across the age ranges.Respondents were also asked in what ways they used computers for whakapapa research (Appendix 2, Question 16). Respondents were given a range of options and these are ranked according to frequency in Table 6 below.

Table 6. Ways of using computers for genealogy

Though at least some respondents are using library websites for this purpose (see 5.4.4 Librarian produced materials used by whakapapa researchers), it is not clear which other internet sites whakapapa researchers use. It is perhaps worth noting that one respondent reported that they were the webmaster of a whānau/family website that contains whakapapa information. The researcher’s library and whakapapa research experience suggests that this kind of “homegrown” resource may be a growth area in terms of whakapapa resources online and again, this is an area that could be the subject of future research.

5.5.2 Use of the library catalogue

Chart 15.

Why this discrepancy should occur is not able to be determined but this was also the case in Kuglin’s study. In terms of library catalogue use, perhaps some tool other than a questionnaire may be more useful in accurately recording how often whakapapa researchers or genealogists employ this in their research. In comparing the results from this study with that of Kuglin, catalogue use by whakapapa researchers seems to be higher than that of the genealogists Kuglin surveyed. In Kuglin’s study over 50% of respondents reported that they “never” or “seldom” used the library catalogue. Only 32% of respondents in this study used the catalogue this infrequently.

Why this discrepancy should occur is not able to be determined but this was also the case in Kuglin’s study. In terms of library catalogue use, perhaps some tool other than a questionnaire may be more useful in accurately recording how often whakapapa researchers or genealogists employ this in their research. In comparing the results from this study with that of Kuglin, catalogue use by whakapapa researchers seems to be higher than that of the genealogists Kuglin surveyed. In Kuglin’s study over 50% of respondents reported that they “never” or “seldom” used the library catalogue. Only 32% of respondents in this study used the catalogue this infrequently.Use of the library catalogue and shelf-browsing were ranked equally highly in terms of usefulness by respondents in question 10. By way of further comparison respondents were asked in different questions how often they found information useful to their research by browsing the shelves or searching the library catalogue (Appendix 2, Question 17 & 19). Again, respondents perceived that they had similar levels of success with shelf-browsing as with catalogue searching (Chart 16).

Chart 16.

The results from these questions differ noticeabley when compared with Kuglin’s research. Kuglin found that 58% of respondents “frequently” or “usually” found useful information by shelf-browsing whereas this study has only 25% doing so. Also Kuglin’s data has 31% of respondents “frequently” or “usually” successfully finding information by using the computer catalogue whereas 39% of respondents in this study claimed that this strategy was “frequently” or “usually” successful. Overall, Kuglin’s study shows shelf-browsing as the more successful search strategy, where this study shows whakapapa researchers enjoy similar degrees of success with both strategies. There is no way of determining in the current research if this is because whakapapa researchers are better at shelf-browsing, or are not as good at catalogue searching, or if some other factor is at play. The relative success rates of shelf-browsing and catalogue searching clearly requires further investigation.

The results from these questions differ noticeabley when compared with Kuglin’s research. Kuglin found that 58% of respondents “frequently” or “usually” found useful information by shelf-browsing whereas this study has only 25% doing so. Also Kuglin’s data has 31% of respondents “frequently” or “usually” successfully finding information by using the computer catalogue whereas 39% of respondents in this study claimed that this strategy was “frequently” or “usually” successful. Overall, Kuglin’s study shows shelf-browsing as the more successful search strategy, where this study shows whakapapa researchers enjoy similar degrees of success with both strategies. There is no way of determining in the current research if this is because whakapapa researchers are better at shelf-browsing, or are not as good at catalogue searching, or if some other factor is at play. The relative success rates of shelf-browsing and catalogue searching clearly requires further investigation.Respondents who “never” or “rarely” used a library catalogue were then asked what reasons they had for not utilising this tool. 12 respondents answered this question (Appendix 2, Question 20) despite the fact that only half of these had previously reported that they used the catalogue “never” or “seldom”. Due to the small number of respondents who “legitimately” answered the question as requested, it was decided by the researcher to allow all ticks to be included in the analysed data (Chart 17).

Chart 17.

Legend

Legenda. I can’t figure out how to use it

b. I don’t know what words to use to do my search

c. I can never find what I want

d. I prefer to browse the shelves

e. The catalogue doesn’t “understand” Māori words.